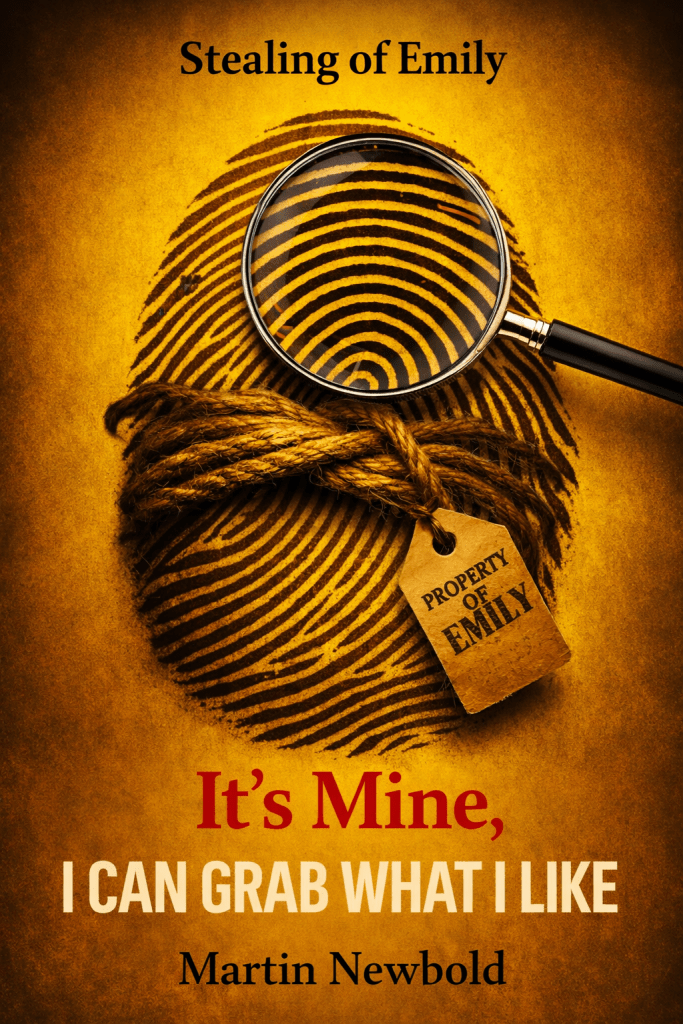

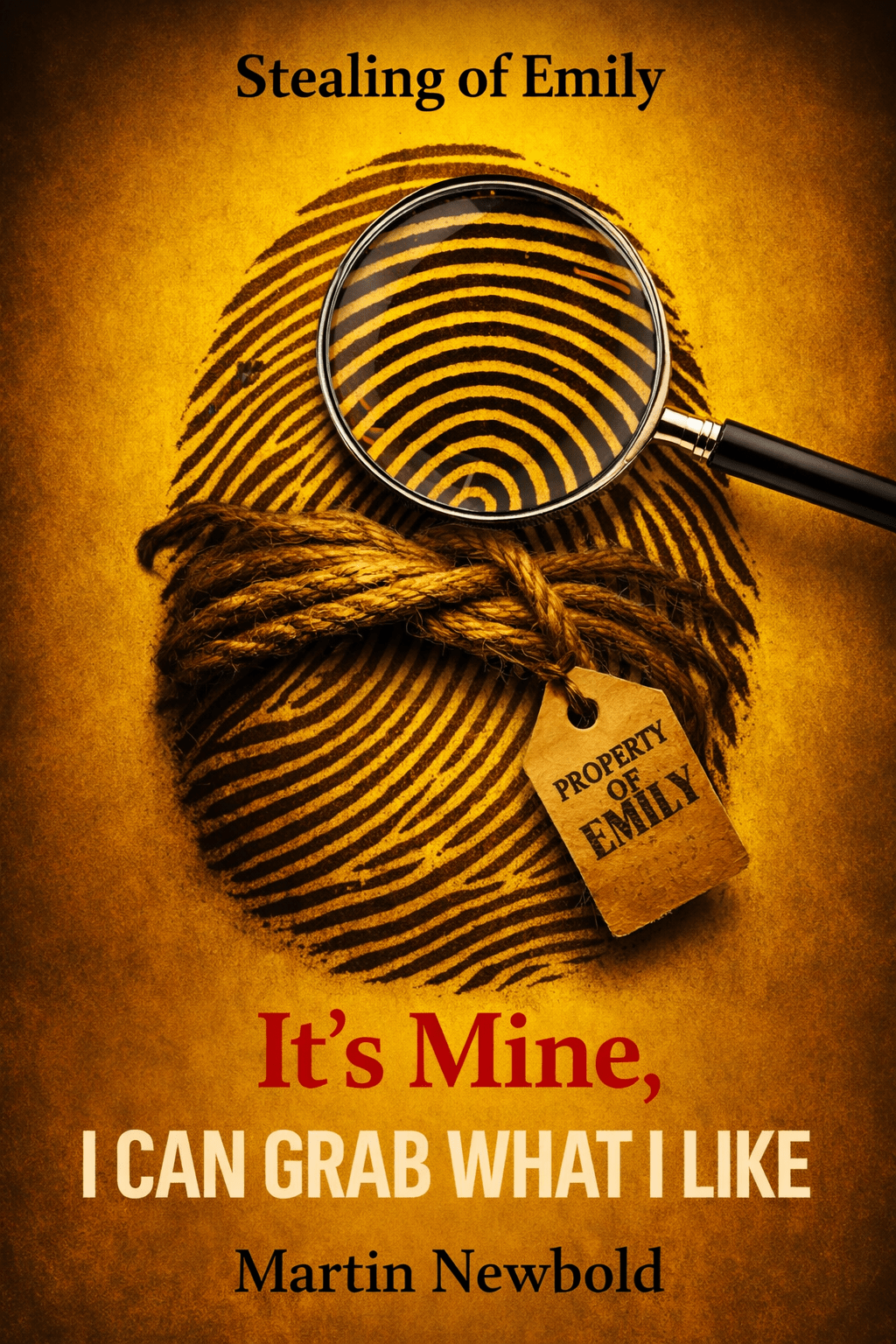

Coming Soon – It’s Mine. I Can Grab What I Like — Martin Newbold

It’s Mine. I Can Grab What I Like is not a conventional exposé, nor is it a memoir in the ordinary sense. It is a forensic, deeply unsettling examination of how modern institutions can fail catastrophically without ever appearing to do so. The book does not rely on sensational revelations or hidden-camera moments. Instead, it exposes something far more troubling: the quiet, bureaucratic mechanics by which responsibility evaporates, accountability is deferred indefinitely, and real people—especially children—are reduced to data points that can be moved, erased, or “resolved” without consequence.

At its core, the book is about disappearance. Not disappearance in the dramatic, cinematic sense, but a more insidious form: administrative disappearance. Newbold argues that in the contemporary state, people no longer need to be physically removed to be lost. They can be deleted procedurally. A record changes. A status updates. A file is “exited.” A dashboard remains green. And the person at the centre of it all ceases to exist in any system that carries responsibility.

What makes this book compelling is not only its subject matter, but the way it is constructed. Newbold does not write as a distant commentator. He writes as someone who has spent years inside the machinery he is describing—writing letters, filing requests, chasing replies, analysing responses, comparing documents, and noticing patterns that most people never see because they are never meant to look across systems. The book reads like an accumulation of pressure. Each chapter adds another layer: another system, another process, another polite response that leads nowhere. Individually, each interaction might look mundane. Taken together, they form a picture that is both chilling and coherent.

The early chapters focus on the mechanics of record-keeping and decision-making in education and safeguarding. Newbold introduces the idea of “ghost schools”—entities that exist administratively but have no meaningful physical presence or capacity. These are not necessarily illegal creations; they arise from licensing and registration loopholes, digital convenience, and outsourced systems that prioritise compliance over reality. Children can be enrolled on paper into places they cannot attend in practice. Attendance then becomes impossible, and impossibility is treated as failure. Automated rules trigger exits. Responsibility moves elsewhere. The child has not “gone missing” in the traditional sense; they have been processed out of sight.

From there, the book widens its scope. Newbold examines how similar logic appears across multiple domains: policing, complaints handling, archival systems, and government oversight. A recurring theme is the difference between recording and acting. Information is logged. Intelligence is entered. Concerns are “noted.” But action does not follow. Systems such as police tracking databases or safeguarding registers create the impression of diligence while simultaneously insulating institutions from obligation. The presence of a record becomes a substitute for response.

One of the most powerful aspects of the book is its attention to language. Newbold dissects the phrasing used by institutions—phrases like “we have recorded your concerns,” “this matter has been logged,” or “the information has been passed to the relevant department.” These sentences appear reassuring, even responsible. Yet the book demonstrates how they often function as endpoints rather than beginnings. Once something is logged, it is considered handled. The burden quietly shifts back to the individual, who must now prove not only that harm exists, but that the system’s acknowledgement of it was insufficient.

As the narrative progresses, Newbold begins to trace these patterns upward, toward national and international levels. He explores how high-level policy decisions, particularly those shaped by transatlantic alignment in the late 1990s and early 2000s, introduced managerial logic into areas that once depended on human judgment and legal scrutiny. Speed, targets, throughput, and risk management replaced care, due process, and open challenge. Children became “cases.” Families became “risks.” Courts became bottlenecks to be streamlined rather than safeguards to be respected.

This section of the book is careful, methodical, and deliberately restrained. Newbold does not claim secret conspiracies or hidden cabals. Instead, he shows how policy frameworks, once adopted, create predictable incentives. When institutions are judged on outcomes rather than processes, shortcuts become attractive. When scrutiny is costly, secrecy becomes efficient. When harm is diffuse and responsibility fragmented, no single actor feels compelled to stop the machine.

A significant portion of the book examines archives, records, and withheld material. Newbold’s interactions with major institutions—particularly in relation to historical records involving senior political figures—are used to illustrate a broader problem: acknowledged existence without disclosure. He shows how archives can confirm that documents exist while simultaneously refusing to release them, citing restriction codes, exemptions, or indefinite review. The reader is left with a strange paradox: proof that something is there, combined with absolute barriers to seeing it.

This dynamic mirrors what happens at ground level. Just as a police database can show that information was received without showing what was done, an archive can show that records exist without revealing their content. In both cases, transparency is partial and performative. The system discloses just enough to protect itself while withholding what would allow meaningful challenge.

One of the book’s strengths is that it does not rely on outrage alone. Newbold is meticulous in distinguishing between what is proven, what is inferred, and what is withheld. He repeatedly points out where evidence stops—not to weaken his argument, but to strengthen it. Absence itself becomes part of the story. When records are known to exist but cannot be accessed, that fact matters. When responses are promised but never delivered, that silence matters. When reforms are announced without engagement with those who raised the original concerns, that gap matters.

The human cost of all this is never far from view. Although the book engages deeply with systems and structures, it never lets the reader forget that these abstractions affect real lives. Children who vanish from registers do not vanish from reality. Families who are ignored by complaints systems do not stop suffering because a database entry exists. Funds held in trust do not become morally neutral because their beneficiaries are “untraceable” on paper.

In later chapters, Newbold turns to money—not in a sensationalist way, but as another indicator of systemic failure. He examines how statutory funds intended for children can remain unclaimed or misallocated when identity records are inaccurate or displaced. Again, the pattern repeats: a system functions exactly as designed, producing outcomes that are technically compliant but ethically indefensible. The question “where did the child go?” becomes inseparable from “where did the money go?”—and in both cases, the answer is buried under layers of administrative process.

What gives It’s Mine. I Can Grab What I Like its unsettling power is its refusal to offer easy villains or comforting resolutions. There is no final revelation that ties everything up neatly. Instead, the book leaves the reader with an uncomfortable recognition: these systems persist because they work—for institutions, not for people. They reduce risk, manage exposure, and distribute blame so widely that it effectively disappears.

The title itself encapsulates this reality. It is not a boast made by a single individual, but a philosophy embedded in structures. “It’s mine” refers to data, authority, discretion, and control. “I can grab what I like” refers to the ability of institutions to take responsibility, records, or even people into their systems—and then deny accountability for what happens next.

For readers interested in child protection, digital governance, public administration, or civil liberties, this book offers a rare inside view of how harm can be normalised through procedure. For those who have ever filed a complaint, submitted evidence, or tried to navigate a bureaucratic maze, it will feel uncomfortably familiar. And for anyone who believes that transparency and accountability are cornerstones of a functioning democracy, it poses a stark challenge: what happens when systems are transparent only about their own processes, not their consequences?

It’s Mine. I Can Grab What I Like demands patience and attention. It is not a light read, nor is it meant to be. But for readers willing to follow its trail of documents, silences, and patterns, it offers something rare: a coherent explanation of how modern systems can fail without breaking, and how injustice can be produced not by rogue actors, but by well-maintained procedures doing exactly what they were designed to do.

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments if this interests you, or leave a review if you’ve read the book!